Hey everyone. Today’s essay is by request. Winter’s earlier, darker hours came up in a recent conversation with a friend and we talked about how it’s affecting us. Usually I don’t think about it much—I can’t control the seasons and I secretly love being in bed by 8. But it made me wonder whether the darkness is why I’m avoiding news in the evenings, skipping afterwork meet ups and losing motivation for morning runs. Some people describe it as a natural time for hibernation, others nicknamed it hell on earth. Maybe rolling with the punches isn’t the best strategy here? Let’s unpack a collective feeling my friend put so eloquently: “I just really need more light”.

In today’s essay:

Creating your own day/night contrast.

Winter depression: real or perceived?

How winter darkness actually works for you. (below paywall)

A day in my life following the research. (below paywall)

I know for a fact that the darker hours are a hot topic in everyone’s group chats right now, because apparently we are once again collectively shocked by how early it gets dark. Like this tweet going viral each winter without exception since 2016. So I’ve been thinking about how darker days affect health - if at all - and how the accumulation of our attitudes and behaviours on winter impact our long term life quality. After all, we spend about 1/4th of our lives in winter time. How sad would it be to hate a fourth of our lives by default?

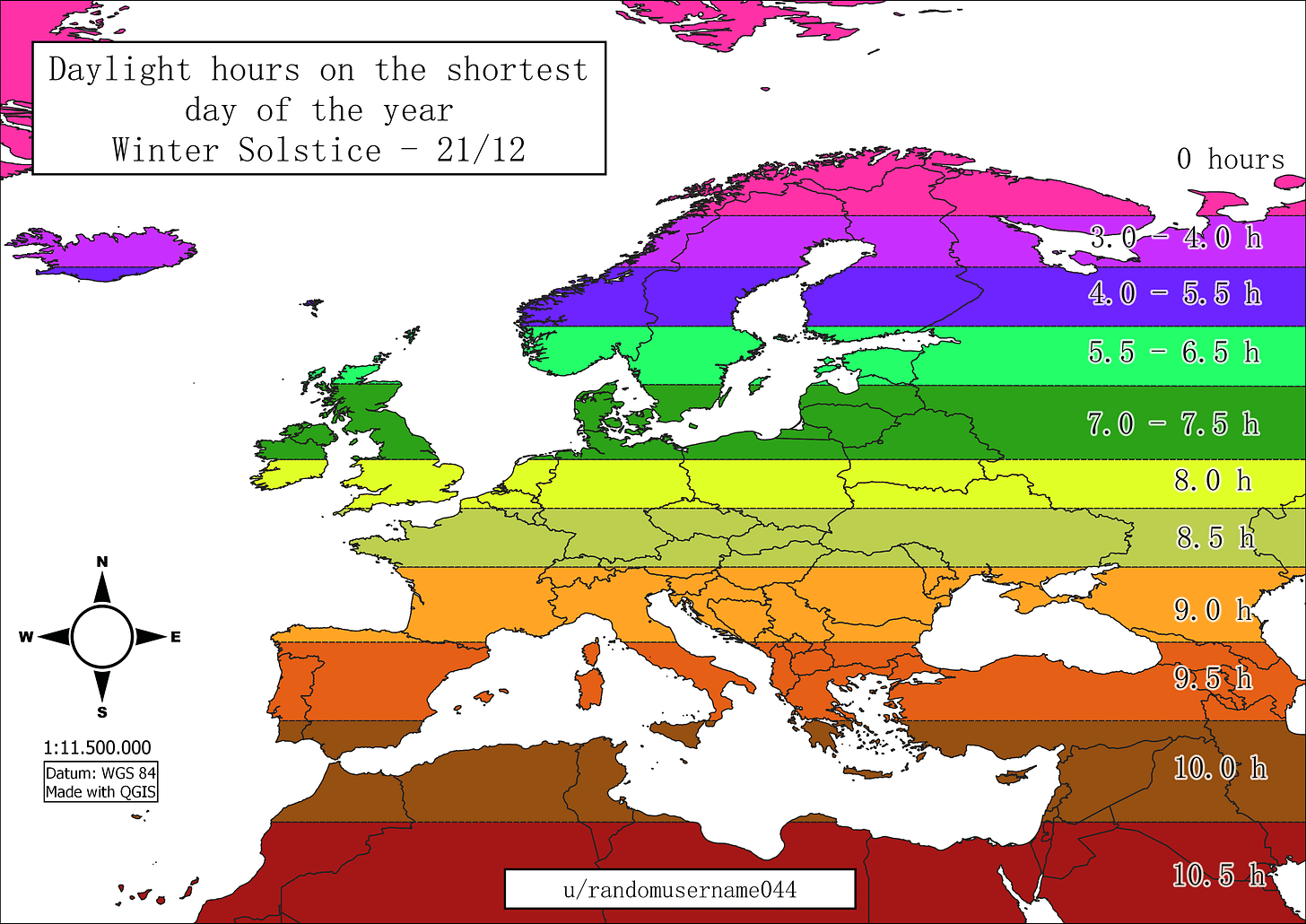

I don’t think this will be a “how to stay motivated when it’s dark” post. I figure it’s more useful and fun to share interesting data that can inform you enough to make your own decisions on how to handle this time of year. Making winter work for you, instead of working to get through winter, you know? Worst case scenario, you know you’re not alone. Best case scenario, you realise you don’t have it as bad as your peers in Scandinavia.

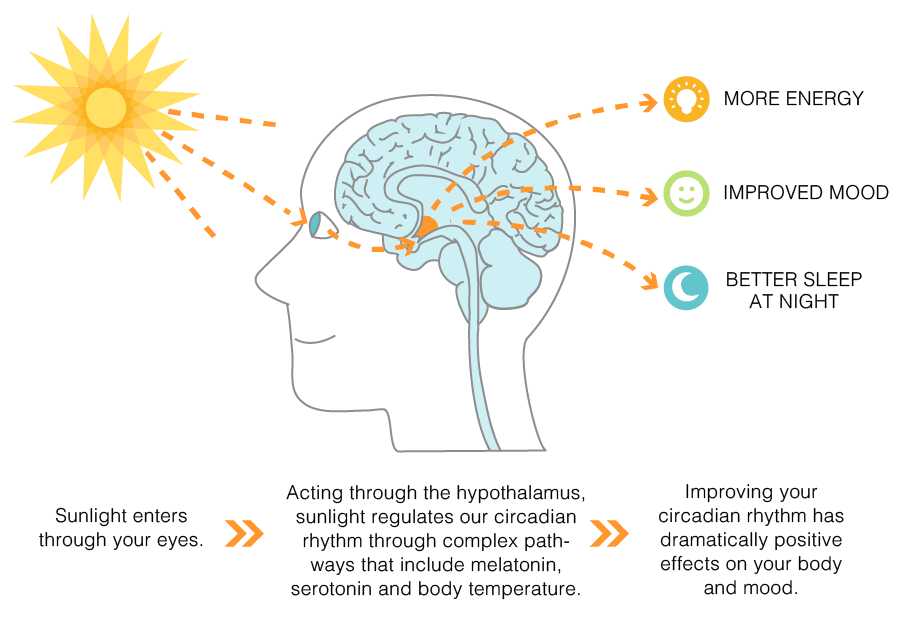

Unfortunately some of the winter gloom and doom is a biological process that literally hinges on the amount of sunlight we receive on a daily basis. Sunlight entering our eyes regulates hormones, which in turn rules our circadian rhythm and things like sleep and feelings of happiness and appetite. When there isn’t enough natural light (winter), our levels of melatonin increase, our levels of serotonin decrease, and our biorhythms get really confused. Especially for those who are evening chronotypes, as they are more prone to depression than morning-oriented people. Overall, this leads to disrupted sleep, feeling less happy and having lower energy. And although this sounds pretty standard and maybe even obvious, these biological changes impact far more than our subjective life experience. Research in mice has shown that deviating from a 24h innate circadian rhythm can lead to a 20% decrease in lifespan. And MIT compares these kinds of changes to our light/dark cycle to daily mini jet lags. This means that it’s incredibly important for us to flexibly respond to these changes, not just between seasons, but also between daily fluctuations brought about by our plans and life in general. It might also be important to note that our biorhythm isn’t just impacted by when we sleep, it’s also influenced by diet. A high-fat diet has been shown to throw our circadian rhythm off-beat, for example. But that’s not the focus of today’s essay.

What I personally take away from this information is that it’s paramount to create an inner locus of control when it comes to our circadian rhythm. To stay in control of our nights and days ourselves, rather than at the mercy of the weather. That means being in the light when it’s day (go outside, work by windows), and being in the dark when it’s night (less artificial lighting). Lynne Peeples, author of The Inner Clock, emphasises that contrast creation is key: brighten your days and darken your nights, and you will experience a vast amount of health benefits. The contrast you’re creating is between your 12 hour day and 12 hour night, not the 7 hour day and 17 hour night the weather is trying to force upon you. And there are more ways you can create that contrast, for example using the rest/activity circadian rhythm: keep active during your 12 hour day, then rest during your 12 hour night. That evening run you were thinking of is a great idea. It might be dark outside, but you still have 3 hours left in your day. The book also advises things like daylight lamps to increase the amount of hours in your days, and blackout curtains to keep out the light pollution from ruining your 12 hour nights.

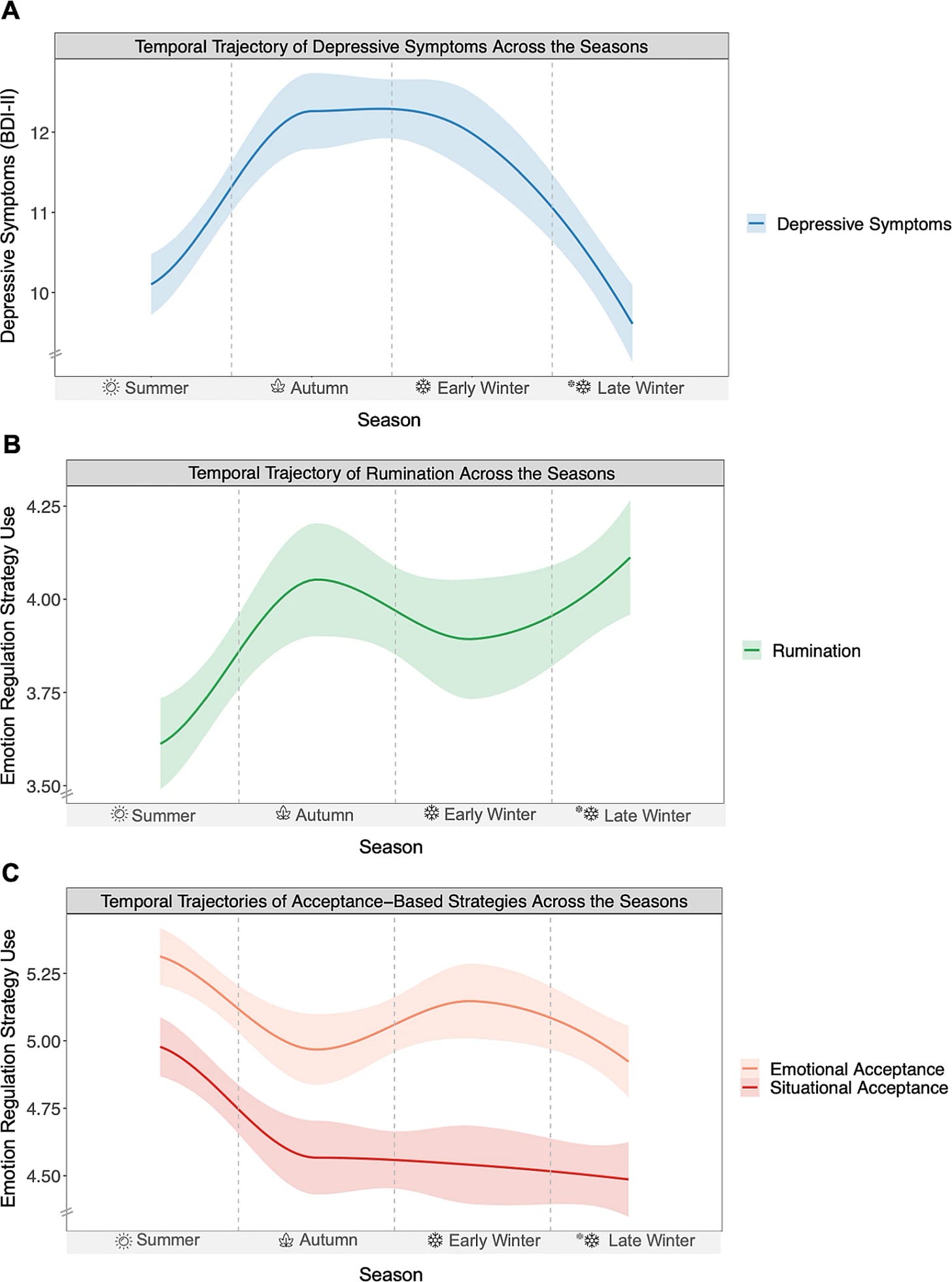

One of the most notable changes in winter is the dip in mood and lust for life. Research shows that depressive symptoms increase in autumn and early winter, while rumination is highest in late winter, when emotional and situational acceptance are also low. I know this sounds depressing, but hear me out: the same research proves that those with higher levels of acceptance are able to beat the winter blues better. On the contrary, those who engage in suppression or reappraisal (trying to feel better) experience higher levels of depression. Simply put: the more you try to fix the winter blues, the worse it gets. Acceptance of the season and its effects on you, are key to feeling better about them.

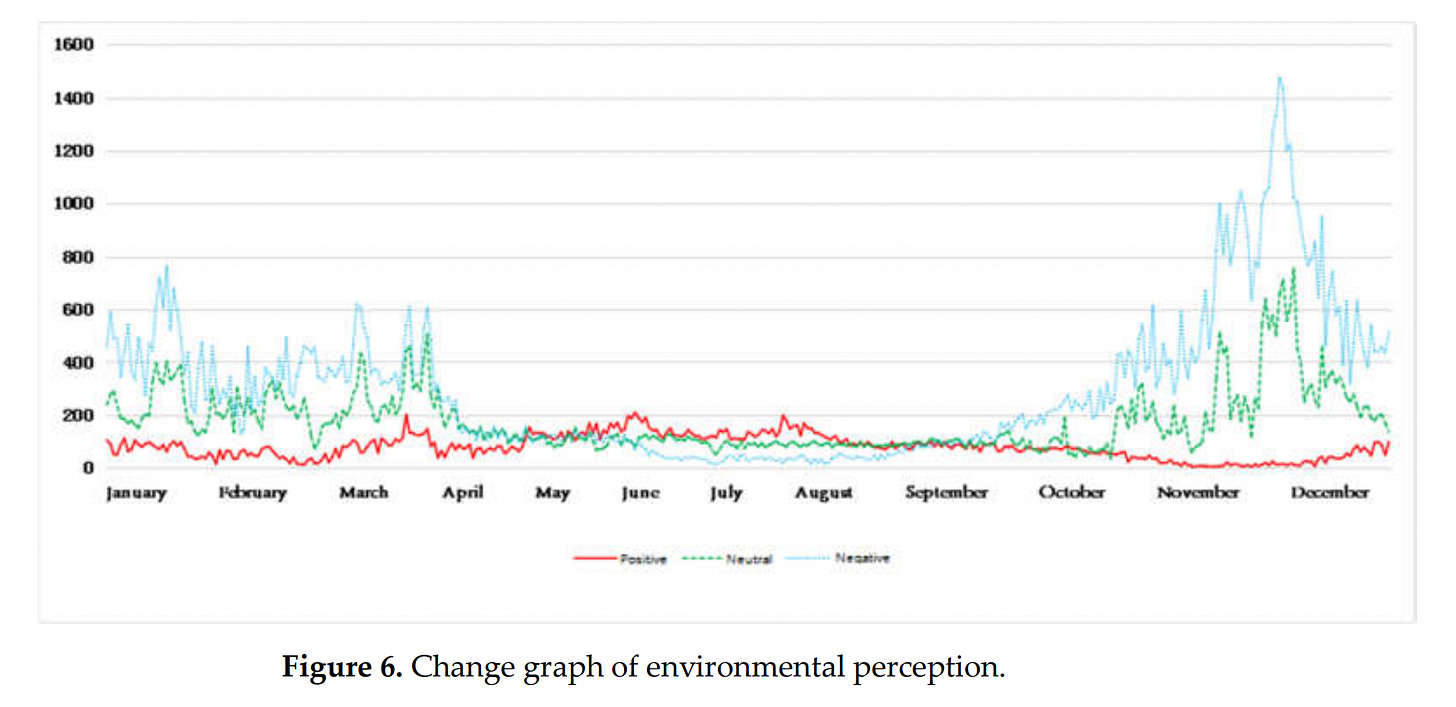

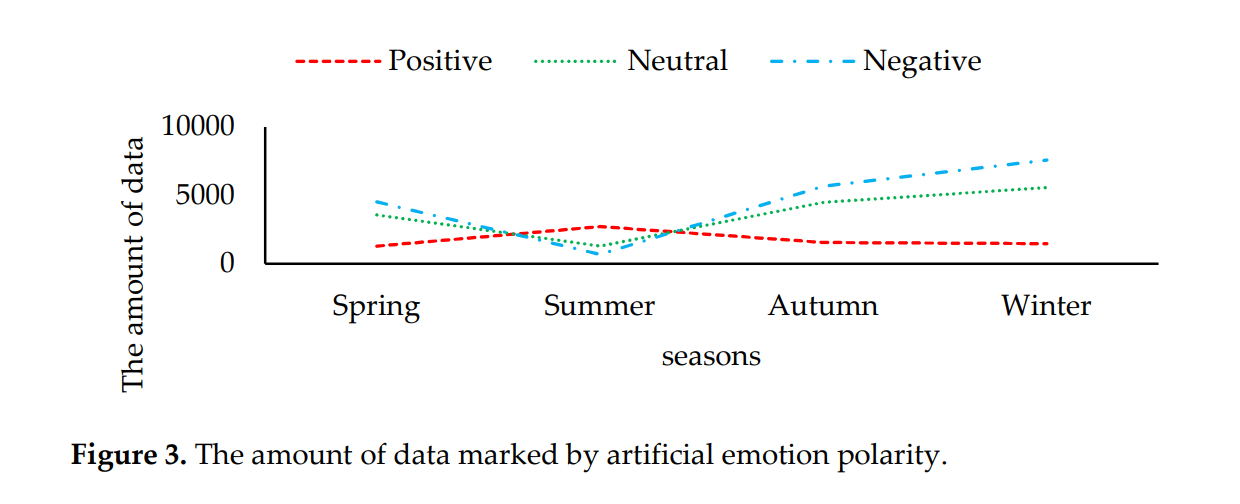

Here are some thought-provoking findings that might make it easier to accept winter. In wintertime, your default perception becomes more negative. A neutral environmental occurrence, such as haze, is perceived as neutral in summer but negative in winter. And it’s not just that. The researchers gathered their data by tracking mentions on social media platforms, which means that not only do we perceive things to be more negative, we also talk about it more, which in turn makes our perception of the public’s emotions more negative. Next time you think everything and everybody is bad, could it just be your brain’s perception of things? Could it be that your environment seems more negative than usual? Are you the one saying more negative things?

If you’re starting to notice, perception is a recurring theme. Let’s look at the actual stats for winter depression.