Happy Sunday eve everyone. I’ve missed you. I had a break in-between newsletters because of a small spinal injury. Thank you for being patient with your temporary patient.

Today’s essay is split into two parts:

Does working hard always lead to burnout? (Part I)

Which personality traits make you more susceptible to burnout? (Part I)

Science-backed strategies to achieve without burning out. (Part II)

I read a spicy stat last week: 2.7% of working people experience 0% burnout. Around 3.5 billion people are employed globally. If we extrapolate this, about 95 million people experience 0 stress-related exhaustion. Usually we focus on how many of us are exhausted, but let’s focus on the minority that isn’t, for once.

We could assume that these 95 million people exist on either end of the bell curve: they are either less ambitious or hard-working or don’t care about achievement, or, they have already gone through the work and achieved (or are privileged enough to live) a life that no longer requires exhaustion. In short, they are either behind or ahead of you. But, in order for that line of thinking to hold up, the following would also have to be true:

only those with high-level jobs experience burnout,

the hardest workers are the richest,

anyone who is rich today had a burnout first,

work-related success makes you happy,

hard work always leads to burnout.

We know, intuitively and statistically, that those statements are irrevocably false. So if that bell curve theory doesn’t hold, who are these people? Are they outliers scattered throughout various levels of success, randomly, resiliently? Might there be something to learn here?

I don’t believe the lesson is to work less hard, or to be less ambitious. Everybody thinks they are the hardest worker in the world. In fact, 3.2 billion burnt out people believe they work harder than you. Rather, should we start wondering if 97.3% of people are running on hamster wheels instead of a track with a finish line? If burnout would, in fact, be a good strategy to reaching goals, wouldn’t more of those 3.3 billion people be… not burnt out?

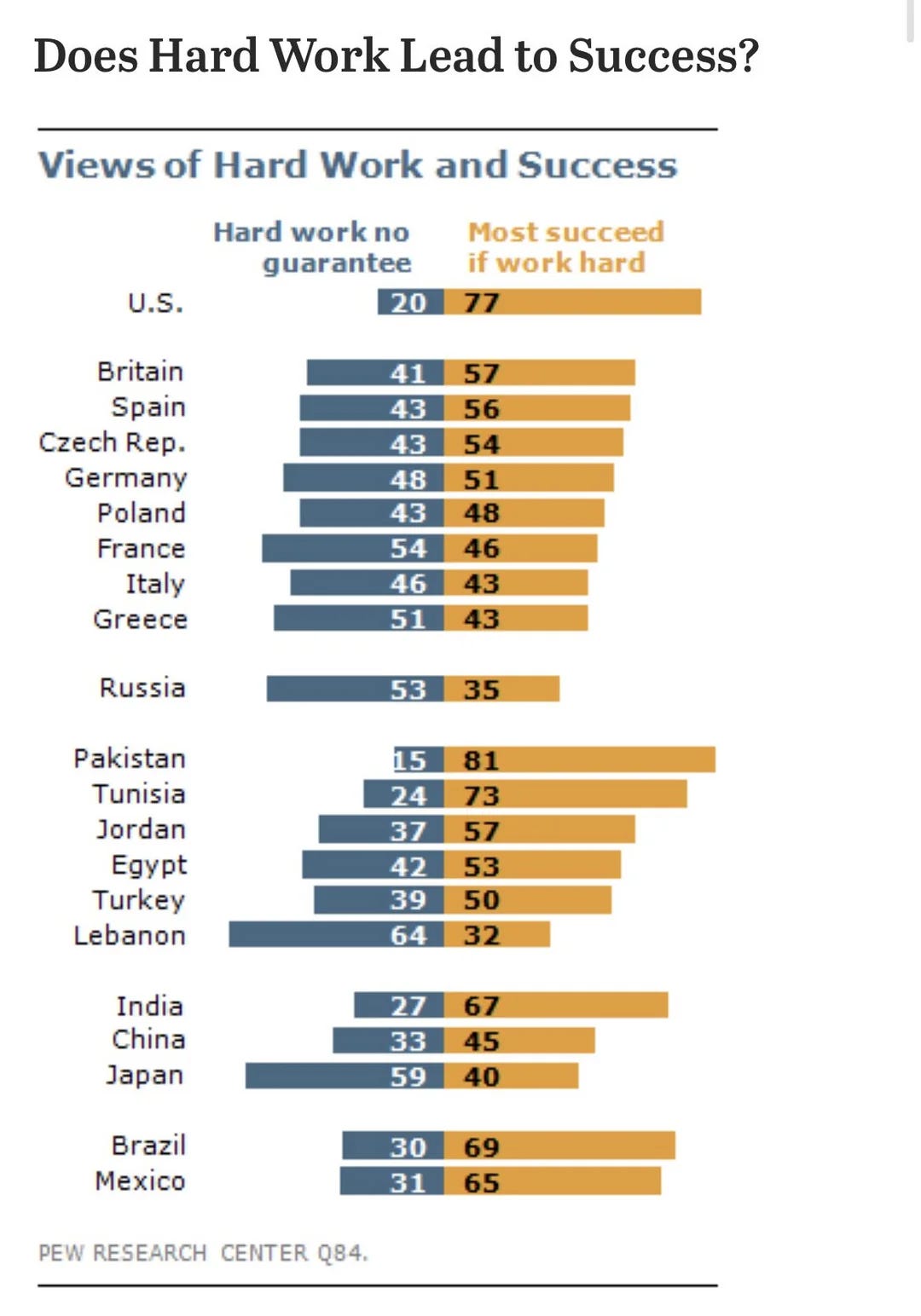

It seems that most people are aware of the fact that hard work and success are correlated, but not causational. (This research is from a decade ago, and I have a feeling that the American Dream might not be so alive and well at this point.)

Burn-out is clinically described as the trifecta of: exhaustion, detachment and decreased personal accomplishment. Exhaustion means feeling drained, overwhelmed, and lacking energy. Reduced personal accomplishment involves feeling a sense of ineffectiveness and a lack of achievement no matter how hard you try. Depersonalisation, also called detachment, is the feeling of becoming cynical, hardened, or distant towards things and people you should normally care about.

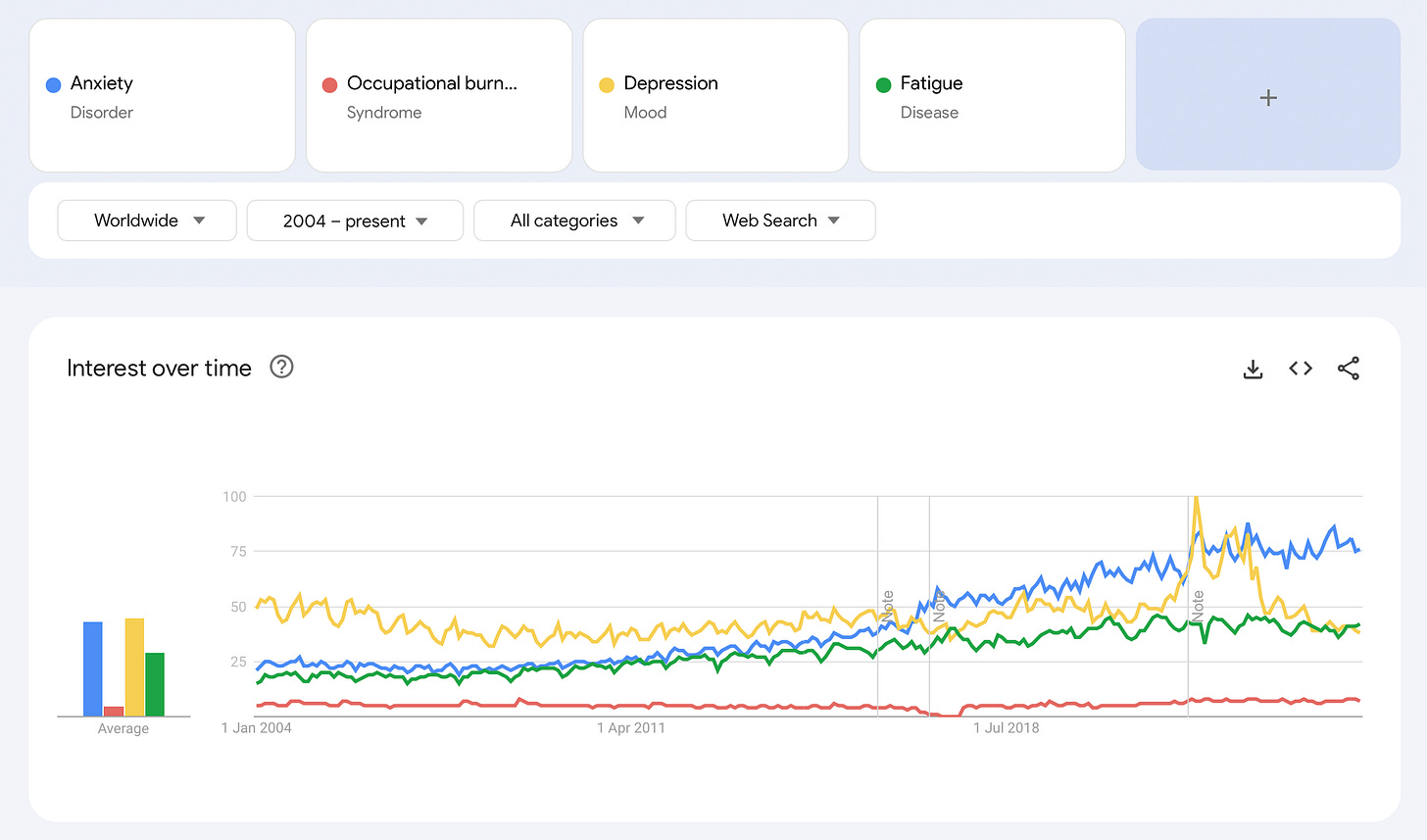

Consequences of burnout include structural and functional brain changes, systemic inflammation, immunosuppression, cardiovascular disease and premature death. Not a great way to live now, nor for long. Looking at Google Trends for the past two decades, it’s interesting to see that ‘burn-out’ hasn’t gotten more hits, despite every news outlet and company declaring a sharp increase amongst employees. So why is that? Are people not aware of the term? Can we only name proxy emotions? Or, do we simply not realise how impactful stress is until it’s too late? Searches for ‘anxiety’ have been on the rise since 2011, comfortably overtaking both depression and fatigue, even during covid.

It’s very clear. Humankind is anxious. And it checks. Findings say that burnout is associated with sustained activation of the autonomic nervous system and dysfunction of the sympathetic adrenal medullary axis, with alterations in cortisol levels. In normal language: burnout is the resulting state of prolonged exposure to stress. So yes, we will be picking up on stress and anxiety (and googling it) long before burnout happens. So why aren’t we able to stop it before it’s too late? Well, because it seems that the call is coming from inside the house.

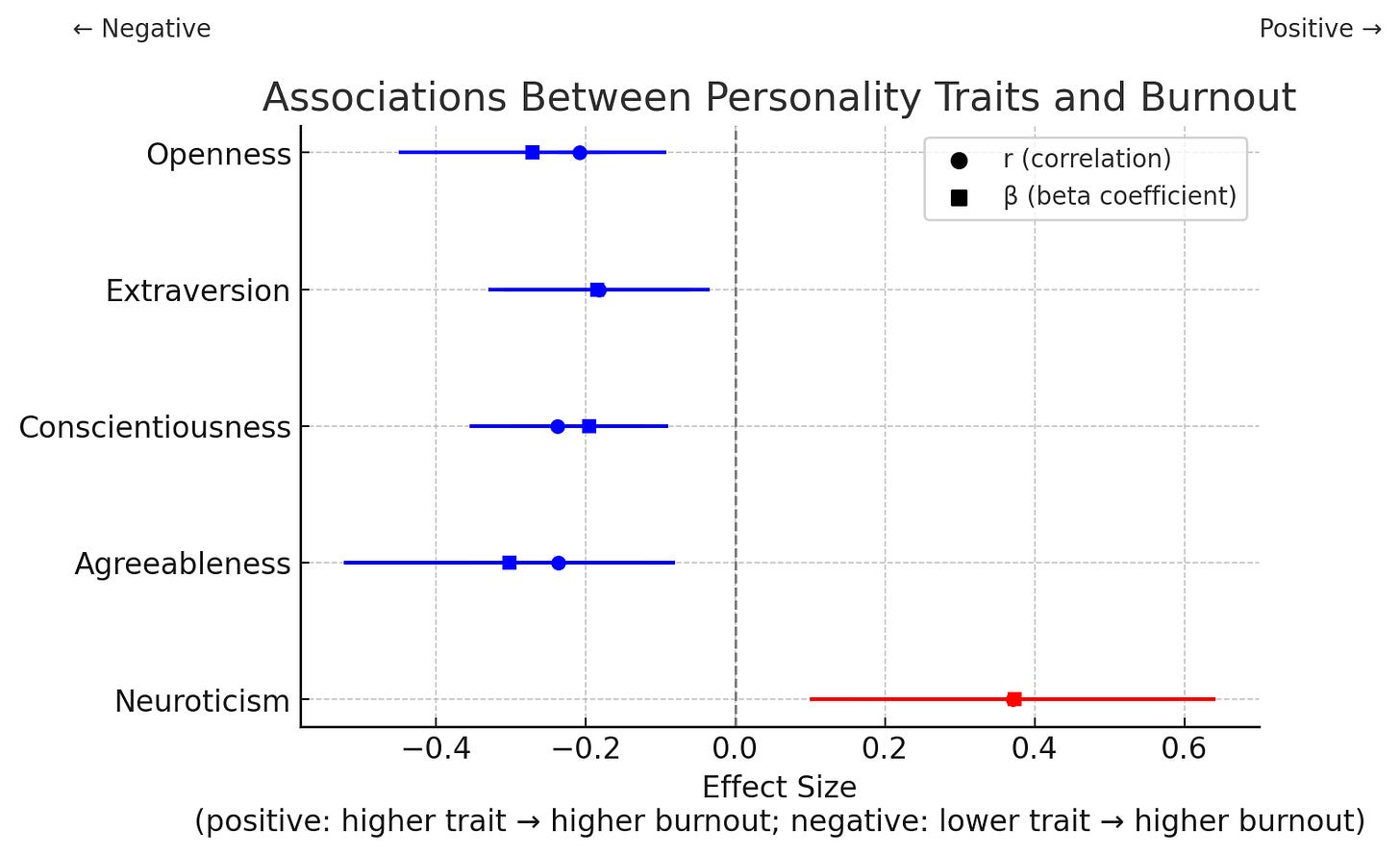

According to this research, burnout isn’t actually caused by hard work more so than by our inability to regulate our emotions about said work. Equal hard work, but with correct emotion-regulation strategies (ERS), has shown to significantly mitigate burnout risk. This teaches us that if we’d work on mitigating anxiety and stress from the inside out, we’d be much more equipped to deal with external pressure and potentially curb burnout. So why aren’t we doing so? Well, personality styles might be to blame. Research has found that the Big Five personality traits correlate to your risk of burnout.

From strongest predictor for burnout to weakest:

High neuroticism: tendency to experience negative emotions (worry, stress).

Low conscientiousness: being disorganised and irresponsible.

Low agreeableness: being uncooperative and not compassionate.

Low extraversion: not enjoying social interaction.

Low openness: not being curious and open to new experiences.

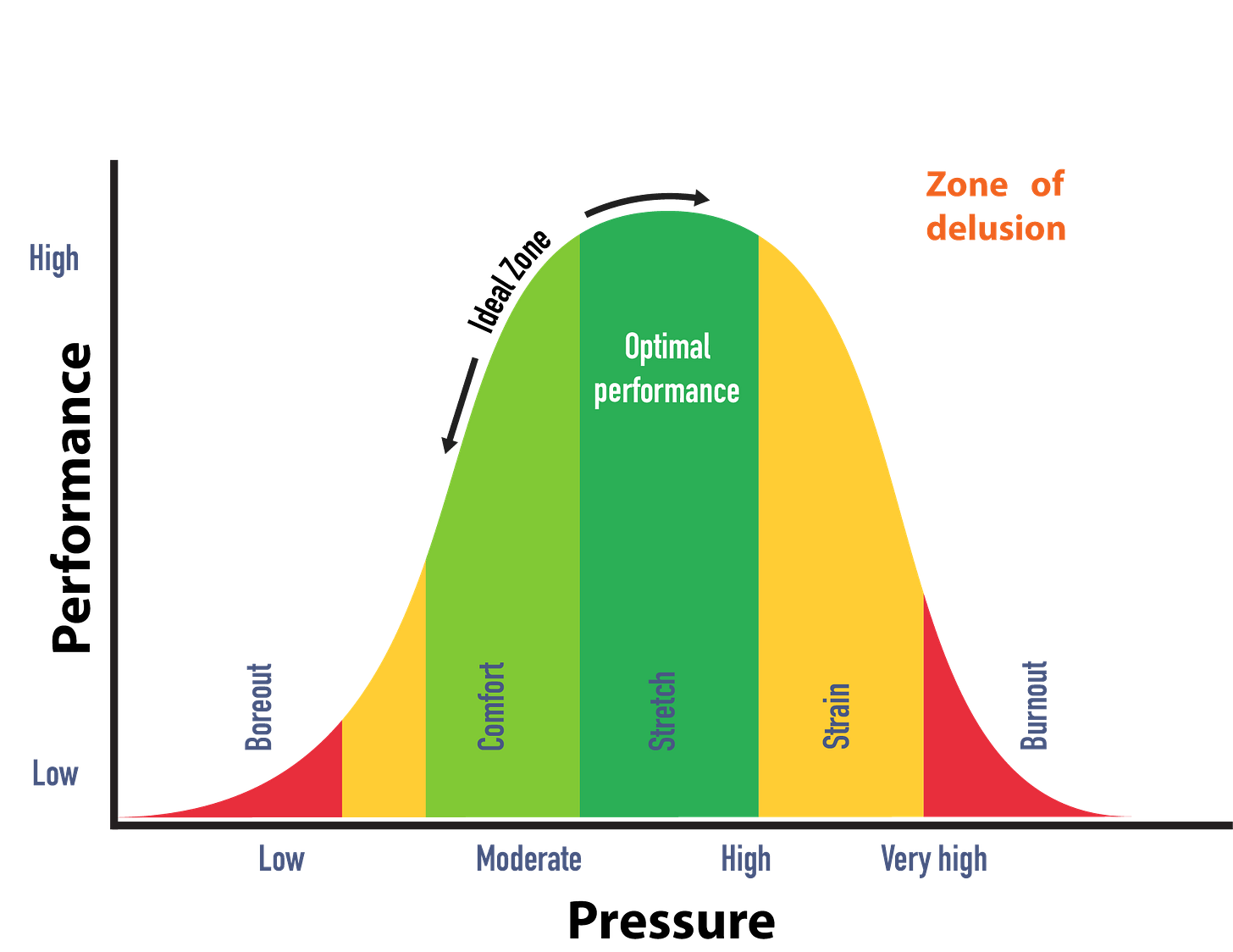

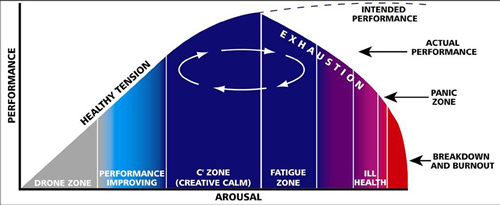

Could it be that instead of feeling overwhelmed by the work, we are actually feeling extreme anxiety about what would happen if we didn’t successfully accomplish the work? From a work quality and quantity perspective, it makes no sense for us to push to burnout. Performance drops when pressure gets too high.

So if work load is not the leading cause of burnout, and burnout is not actually improving the quality or quantity of our work – why are we still burning out? Why are we choosing to put in more hours instead of incorporating serious emotion-regulation strategies? Are we working too hard, or are we trying to outwork a fear of failure? Are we anxious about our work, or about not being able to accomplish what we’d like through our work? Could burning out be an unconscious excuse to not have to deal with how we’d think of ourselves if we didn’t make it? What if, instead of putting in more hours, we’d spend time on emotional regulation, value-driven scheduling and better agreeableness?